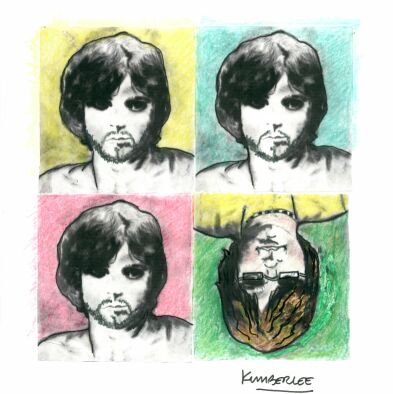

The Bargain

Kimberlee Sweeney-Rettberg

Deep in the hushed corridors of Our Lady of Faith Hospital, past the dimming sconces, across from the Neuro-ICU nurses’ kiosk where silent women scribbled charts, lay the boy. He breathed in time with the respirator–that machine pushing air ruthlessly, rudely, through his body, overruling death. Despite the life-preserving mechanisms, the boy’s brain was completely dead. Nothing yet invented could force it to live. The boy was so young.

Earlier, the neurologists had taken his mother out into the hall to discuss her decision to keep him on life support. It was very expensive to do so. The woman had bristled. Why should they go out into the hallway to speak, then, if there was no possible chance the boy could hear them? Harshly, the mother had discharged her scalding bitterness upon the lot of them. When the room emptied, she sat down on the hospital bed, very close to him, and covered her eyes. In her own way, she was as blind and senseless as her son.

In another city–another state entirely–the rock star, David Druid, lay barely conscious on the thick carpeting of his hotel room, neither any less isolated, nor hardly less brain-dead, than the boy. There was no machinery in David Druid’s hotel room, save the eerie murmuring of a television set projecting surreal images. The rock star lay in an ignoble fetal position, his skinny arms clutched close to his chest and his knees drawn up. Beside him, the phone was off the hook.

By an unhappy coincidence, both young men were very near death. The differences were negligible, except that in the hospital room, a quietly crying parent prayed with rabid intensity, offering anything and everything to bring her son back to consciousness.

Druid had paid for his escape in cash. The price did not bother him, so long as the promised oblivion followed. There had to be that guarantee.

The accouterments of his bliss lay strewn about him: syringes with needles in plastic covers, a bottle of scotch, and three or four Baggies of illicit pleasures. There were no women; not tonight.

Druid’s arm twitched spasmodically for a moment, then settled back to its drawn-in posture. In the next room, his bandmates were experimenting with different copulatory configurations with very young girls.

The boy in the hospital room listed and felt himself in a weird nether land. He was floating somewhere above his hospital bed, peeling at the wainscoting, both seeing and unable to see himself below. From wherever he was, he could hear his mother’s prayers very clearly. He tried, but was unable to squeeze her hand. Once–perhaps a few days ago–he had been able to accomplish this, but the feat was fleeting.

He was in his body, feeling the horrid blasting of oxygen into his lungs, which forced his rib cage to heave with dreadful effort. And then, perhaps to escape the intrusion, he floated back up around the ceiling again. He didn’t care much for the body on the bed. His only wish was to speak words to his mother, to tell her that he was all right, and not to drain her life with grief.

The two young men shared an unfortunate connection in addition to their temporarily shared unconsciousness. Several days earlier, the boy had come to a concert given by David Druid. It was in Chicago–a bit of a drive from the boy’s town–but all of the details had been anxiously planned with his friends. Druid was a hugely popular star. There were pictures of David and his band in the young boy’s room, as well as posters and a pile of CD’s. His mother’s thought Druid’s singing sounded like a large farm animal caught in a trash compactor, but she had allowed him to go to the concert that night anyway.

There had been problems from the beginning of the performance. The promoters had overbooked the event and spectators fought with one another for the same seats. Security guards were no match for the angry crowd. When the band came out on stage, the skirmish turned ugly.

David Druid had looked out over the footlights and the rioting fans. The boy in the front row had been struck in the head, and blood pooled over the hands and uniforms of the security guards trying to jostle their way out of the mob. In that moment, the rock star had felt as though the blood were on his own hands.

And it was. He, David Druid, had caused this to happen.

There had been many people injured that night, even though the performance had been swiftly halted. Chairs and bottles–even people–had been flung up onto the stage, the tour manager frantic to get the band out of the concert hall.

Outside, before they all got back into the bus, David Druid had watched the still-bleeding boy being air-lifted to a medical center in Chicago. Dozens of others had been driven out and loaded into ambulances like so much livestock.

“Come on, David!” But the singer’s eyes remained fixed on the chopper, rising slowly into the chilly air.

And the tour had gone on, finishing out the final two gigs, like a nightmare prolonged. The number of reported injured in Chicago climbed. There had been one press conference after another, much apologetic rhetoric and, in response, the threat of daisy-chains of lawsuits.

The headlines trickled down through every form of media. The final two shows sold out. But David had plunged dangerously to the bottom of a pit of drugged desperation. He was not thinking of the lawsuits or the sold-out shows. He was trying to chemically wash clean the sight of the blood-soaked boy with the split-open skull.

***

The mother was not thinking of lawsuits, either. She was not even angry at the helter-skelter melee in which her only son was injured. She knew it was not unusual at rock concerts. The only thing she questioned over and over again was, why this one?

She watched the boy in his suspended existence between life and death. Maybe this really was Purgatory. But if she looked at him long enough, sometimes it was easy to pretend that he was only sleeping.

***

David Druid turned over in his stupor. He opened his eyes dully, realizing he had no idea what city he was in, what hotel. It did not really matter. He pulled himself partially to his knees to hunt for the Baggies. He tried to roll a joint from one, but his hands were too shaky. The powdery herb fell out into the carpet. There was an open vial of reds near the corner table, on top of the room service menu.

David raised himself on his hands, dragging his legs along, crab-like. Before he reached the table, however, he fell back on the floor. He rolled over on his back, laughing until it hurt. No way he was going to make the distance.

On the floor just a bit to his right lay another Baggie, folded over and stuck together with saliva. The rock star couldn’t remember if it was heroin or cocaine. Or something else. He frowned. If it was coke, he would turn restless and paranoid, with thoughts and actions like a caged tiger. If heroin, he would be safe and warm and comfortable, content to lie for the rest of the night on the hotel carpet, listening to the television.

He stuck a finger into the Baggie and ran his tongue over it. Mmmmm. Couldn’t quite place it. Then the rock star vaguely remembered funneling some cocaine into the smack to make speedballs. That was good. With his left hand he felt around on the carpet for a syringe, then he tied a belt around his right arm. Pop went the plastic top to the syringe; where was the lighter and spoon? The room service tray had a soup spoon. The lighter was in his pocket. There. It was done. As the drugs slid once more into David Druid’s veins, he replayed the scene of the boy with the bloody head.

***

It was nearing dawn in the Neuro-ICU unit. The tired woman had fallen into a restless sleep in the bedside chair. The nurse had gone out.

The boy’s floating had become restless. What remained of him wanted out of the room. He was no longer content to hover in such close confinement. He had tried repeatedly to reach his mother, but the closest he could get was the same tiny squeeze of her hand. Ah, the hospital room had become so small! He pushed at its boundaries as against the walls of a womb. With this last squeeze he had said, Good-bye, I will always love you. He was ready now to leave.

In the hotel room at the end of the hall, David Druid felt perfectly at peace. The thick draperies were drawn, but a sickly light had gathered outside. The television set still whispered.

David lay near the table on his back, limbs spread apart, wearing a sweet smile. With his tousled blonde hair brushed back–almost tenderly–he resembled nothing so much as a very young boy. Deep within David Druid’s mind, others were speaking lovingly to him. The images weren’t clear: it was like looking into a puddle on broken pavement.

Oh, yes, he heard himself answering. So much different. She doesn’t deserve the pain, and I have no one to love.

The deal was made somehow. The images melted away; the needle lay crushed on the carpet.

***

The woman leaped, startled, from her chair. All of the machinery in the hospital room sang out. It was like a nightmare: the screaming monitors, the black screen with the flat green line. The nurses forced her back. Doctors streamed past her and she was barred from the room entirely. Sobs shook her body. She knew then he was gone.

Hovering, still near the ceiling above the ICU bed, the boy grew ever more restless. He had been pushing his way against the barriers–testing, stretching them further and further–like a newborn widening its path through the birth canal. Freedom was fast approaching. The doctors circled. Suddenly, he began to laugh, as the electrical shocks bruised his chest, insistently, again and again…

And then it happened. The moment the boy felt his tether finally break, his transformation certain–he saw the other. Not understanding, he lingered a moment, his silent question unspoken, but vital.

“We’ve got him! Pulse faint.” The green line jittered and jumped. “BP unsteady, but leveling out.” The boy could see the woman’s mascara-stained face pressed up against the glass. The intensivists drew back. “Take him off the respirator,” the dark-skinned one commanded.

“Are you sure, doctor? He hasn’t been breathing on his own since–”

“I said, take him off. I felt–his chest rhythm. It seemed unimpaired. The lungs sound clear.”

The respirator was removed. The boy’s rib cage heaved violently for a moment. And then the screen which monitored the young man’s brain activity rolled into a steady, gentle pattern. The other intensivists on the team stared at the monitors, at the boy’s pale face, and at the respirator, unbelieving. The pulmonologist with the brown skin let out a raking, shaken breath, and muttered some instructions to the nursing supervisor before turning away. In another moment, he was down the hall and calmly searching for a pack of cigarettes.

As soon as the door opened, the woman’s face crumpled into incredulous, weeping joy. The staff physicians’ eyes darted from one face to another. Who the hell was that doctor?

***

There was a large crowd gathered in the lobby of the hotel. Within minutes, the paramedics guiding the gurney passed by and slid the stretcher into the waiting ambulance. Jaylen Crowe, the band’s tour manager, hunched beside the shrouded form as the ambulance drivers switched on the siren and whined out of the hotel parking lot.

“Can I pull his blanket down for a minute, please?” he asked.

One of the paramedics riding with them in the back of the vehicle nodded. Crowe coaxed the corner of the plain woolen blanket back and puzzled over the rock star’s countenance. David Druid, found dead in his hotel suite–dead from a drug overdose–still wore that strangely satisfied smile. The soft, pink Cupid’s bow of the lips and cheeks making his face so utterly and completely boyish.

The bargain had been a fair one.

Illustration by Kimberlee Rettberg