The Fall

Asher Black

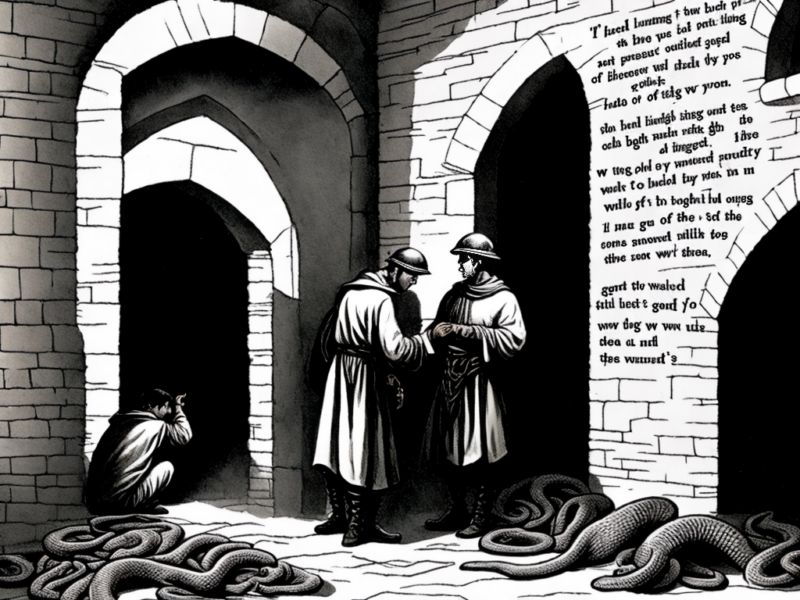

They’ll be coming for me, probably tonight. Maybe in the morning. If it’s night, I’ll die by accident. They’ll make it convincing. A stroll too near the low parapets on the crumbling side of the wall. Strong liquor on my clothes. Word will pass that I complained of being overworked and tired. He was young and small for his age. He couldn’t hold his drink. If anyone raises an eyebrow, the fact will follow that I wasn’t seen in public these last two days. I must have been under the weather. There is too much else to think about and every reason not to look deeply.

No such ruse if they come in the morning. They’ll march me out under the sun, that same sun, under which I saw everything. Call me a criminal. Say I plotted treasonously against my lord. Against that thing. Onto the scaffold. Hand me over to the headman, who will ask for forgiveness, not caring if I answer.

They may do worse. They can damage a man. Make a sane person mad. Say I was delusional. Has been for longer than we imagined. I might believe it when they’re through. When they’re done, I won’t know what truth is or whether there is any such thing. Perhaps you will even agree with them. See my unsteady hand, how it shudders from weakness. I simply can’t eat the food. They have fouled it. Besides, it’s not food, as you might think of it. The rats, my brethren in this cage, are too fleet to catch for nourishment. A blinded eye doesn’t help. Nothing prepares you for the beatings from the guards.

Is it not insane? My own urine for ink. And to stain the pages of holy writ, begged reluctantly from the friar. A last request to a country I have failed when I could have saved it. I faced the cross nervously. The friar wanted me to confess, and I told him all my sins I could recall from the beginning as if I were being newly baptized. All my many offenses against God and man, and yet I’ve remembered more since then and wish dearly I’d thought of them. I still believe, which is the final insanity.

This is a tomb from which I will rise tomorrow, a ghost one way or another, in mind and body. I had best get to the point.

The throng was not a happy one. For dread, even though it was unwise to show it. Even the poorest came. Threatened, beaten if need be, or still willing to believe in the privilege of attending his little parade. Hope is food for the starving. We eat hope but breathe the lingering dread.

The procession did not pass the stalls where there was barely enough fish to fill a basket. No fruit. That hadn’t come in months, except for horse apples. There were some greens and bug-eaten turnips. An occasional basket of toads. Meat that smelled good, but you knew it was rat. A grandmaiden smiled if she got a few centipedes or crickets for too high a price.

Those who hadn’t come to trade or with a few desperate coins dug idly in the rotten soil, hobbled about from malnourishment, or festered in their tents with disease. They certainly didn’t go beyond the walls, where the blight is worse, and contagion roves the hills. The petty landlords are barely better off than the merchants. There’s only so much you can collect from tenants and squatters before you starve them off.

I know, because I was a landlord’s son and educated in the Church when there was something left in our pockets to give to God. Before sending us away, my lonely old priest said the Mass for widows, blind men, and those who had no warmer shelter than a few hours in God’s house could provide.

That was after the old King died, the land weakening as he did, and the young prince declared himself Emperor of all he surveys. Two years, lost parents, and nothing for it but to use my cursed intelligence and damned curiosity to survive within the city walls. I wasn’t very big to begin with. I’m smaller now. Chest high to a man, if I still had the balance to stand. I was never a boy, but still counted as one by my years.

First, as you remember, they plowed a new road for His Magnificence. The soldiers looted and tore down the stalls of East Market to make a fitting path. Smooth, they made it. They forced the stallkeeps to clear “the trash,” which was anything spilled to the ground and not picked up by men bearing the standard. Whatever they couldn’t trade or wouldn’t feed to their dogs.

The imperial train marched down that road, arriving under the brightest sun. I don’t think anyone but the prince’s personal guard and his father’s closest advisors had actually seen him up close, and he came now with no advisors in tow. I swear to you, all who bowed before him were blind.

The new imperial banner was a snake wrapped around a sword. The helmets of the soldiers were serpentine to match. The royal fool even had a live snake. The kind that can crush a man and devour him. He danced with it at the head of their line. The procession stopped. The soldiers signaled silence. The Emperor’s slave and mouthpiece, the herald, spoke. He asked what we thought of the Emperor’s fine attire.

An odd question, but it was obvious what he meant. Suit of snakeskins. Mask in the form of a giant snakehead. It was certainly very fine. Glistening in the sun and moist with oils. People said it was the finest silk they had ever seen. A visage and a coat worthy of an emperor. My oath, many bowed and cheered, not from fear or reverence but pride and awe at being ruled by one so magnificently arrayed.

I confess I cheered too. What of it? The soldiers were watching. Among them, two men were also finely dressed. Outlandishly pale, with serpents tattooed above their eyes. No one remarked on them. It would have been an insult to His Supremity’s glamor. Now, the herald, with a showman’s sweeping gesture, announced them as the honored royal tailors. All eyes but mine were upon them. I studied the prince instead.

His eyes shined even in daylight. I was thinking how warm he must be while my own rags barely covered me. It was at that moment I saw his tongue dart quickly from his mouth, long, pink, and fork-tipped. I looked from face to face, soliders and countrymen, but no one else had seen. Just the once, but then I knew the herald’s remarks had deceived us.

I was foolish. No prank or petty theft could compare with the utter unwisdom of letting my voice ring out louder than the breathing and murmuring of the pressing throng. I interrupted his ongoing speech. What could I have been thinking? “The emperor does not wear clothes!” I shouted, and all eyes turned. Soldiers moved, and I turned to run, but I was trapped by the curious mob of bodies, frozen in their interest. Under their stares and those of the pale strangers and doubtless the prince, I was lifted to the shoulders of one of the guards as though I were still a nursing child. Applause erupted. People laughed and clapped, laughter being so rare now. They said it was an understandable mistake for one so young.

Taken the the palace, I thought the punishment would be swift and decisive, but I was made an imperial page. Given new clothes, wine to drink, real food, and the run of the palace within the castle. Most of it, anyway. I was never actually called into the presence of the emperor, and I forgot any nonsense about what I’d seen in the heat while famished. My imagination had got the better of me, and I accepted it. I soon adjusted to my new surroundings. Especially being fed. The meat was splendid. Boiled until it fell from the bone, tasting of heavy brine.

If my dreams were fitful and sometimes filled my bed with snakes, I forgot them by morning and, having no duties imposed upon me and no chores, spent my time running and playing around the parapets. As high as I could go. Then more eating and drinking wine. I was honored as an aimless prodigy by His Supreme Effulgence, an example for other boys, though I never got to play with any of them again, and the soldiers regarded me with a cold tolerance. Indulged but otherwise forgotten.

I grew tired of the battlement heights and had the irresistible urge to wander below the castle. I knew there were dungeons like this one and places below, as with any castle, where unwholesome things occur. That was the attraction. I have confessed this morbid fascination. I am sorry for it.

When I found the catacombs, as they are called… they are not; they’re tunnels… I did something else foolish. I went there every day. I made my absence obvious. No one hindered me. One is not prevented from going down, at least not an imperial page, but on returning, there are direct, searching glances from the guards. A boy pursuing legends, but a conspicuous boy.

The tunnels stink, and the soil is black and oozing. Much smaller than I anticipated. Just large enough for me to crawl through if I duck my head. They go beyond the palace, outside the castle, and even beyond the outer walls. Miles of penetration far below the anguish above, they became the highways of my curiosity. The nagging truth seeped in slowly with the cold of that place.

They are serpent tunnels. Smooth and inhuman, like the Emperor. I knew then why the farmers’ soil festers the land produces nothing but sparse and rotten crops, and the fish flee the nets along the shore. It is not the death of the old King, as the poets say, in those remaining taverns where the soldiers don’t go. The Emperor is the cause.

I should have fled the palace then, like anyone with sense. Reported what I knew. But to whom? I considered going to find my old priest. If he reads this, he will wonder why I did nothing, but I had never tried to leave the castle. The tunnels have no end, and therefore no exit. They ramble circuitously for miles without an opening to the sky.

By then, too, I was so comfortable that I couldn’t muster any credible fear. Food when others are starving makes you foolish, fat, and dull. With something to explore and leisure to do, I was almost happy despite the general misery outside the palace. That my sleep was troubled was solved each morning by a sumptuous breakfast.

I woke two days ago, however, to the rough hands of the guards, handling me like any common prisoner. The general rule is a beating before being thrown in a dark hole like this one, and they were as lavish with their abuse as they had been with their previous indulgence.

I lament the irony of that. Wise beyond his years, they said. Elevated and held aloft by those same hands, but I wasn’t wise. I took pride, and I dined without awareness or circumspection. Pampered at the expense of a weary and suffering people.

I understand they are composing a story about me up there, among the jewels and chandeliers. One of the guards said so. A lay to become an epitaph. A boast in place of mourning.

The sins I have committed were greed, loving my life above honor, and conceit. The conceit of speaking when others were silent. Seeing what no one else saw. No, I did not confess everything to the friar. Tell him, if you could be so kind. I’ve no one now to hear my confession but you. What echoes in my mind now are the sharp steps clacking down the stone stairs. So, it’s to be night and a fall from the heights, after all.

I wonder if, afterward, the meat will fall from my bones. I wonder if I will taste like salt. He will consume us all once we are consumed by the temptations of famine. A remarkable illusion, this princely thing that isn’t human. Say I’m mad. Perhaps I am, but I saw.